What is Adultism?

The power of adults over children.

An introduction for young people [Englisch/English]

Manfred Liebel & Philip Meade

With drawings by Natascha Welz

Translated into English by Philip Meade and Tanu Biswas

Contents

- Preface

- Adultism in a nutshell

- When did adultism start?

- Adultism today

- Why is there adultism?

- What can be done against adultism?

- Glossary

- About the authors and the illustrator

- Cover text

- Imprint

Preface

We, Manfred and Philip, have written a book about adultism. We explain what adultism is below. Here you can find something about our book on the internet: https://bertz-fischer.de/adultismus.

We both work at a university where children’s rights are taught. But we have also worked a lot with children and young people and are fathers ourselves.

The book mentioned above is thick and uses big words and long sentences. Here we summarise the content in simple language. The original text in German was read and corrected by six young people before it was published. These include Jana Reischel, Lijan Christ, Lino F. as well as Linus Budde.

Young people should be able to inform themselves about the topic of adultism. They have often experienced adultism themselves and have their own thoughts about it. But we are also happy when children themselves tell or write about their experiences with adultism. They can do this in a zine or a blog, for example. We already know some.

© Natascha Welz

Adultism in a nutshell

When was the last time you were asked your age?

(In between, we ask a few thought-provoking questions. It’s not a test … you don’t have to answer them.) 😉

Young people are asked their age more often than older people. There is a reason for this. Most societies in the world divide people into groups. They distinguish between children, adolescents and adults. The United Nations says: All people up to their 18th birthday are “children”. So, adolescents also belong to the group of children. Mostly they then say that adults are smarter, can do more and are allowed more than children. That’s why they think they should rule over children. Children are often treated disrespectfully. All this is called “adultism”.

Adultism can be recognised, for example, in the way adults talk to children. When we were younger, we often heard the following sentences.

Adults order children to do or not to do certain things:

- Look at me when I’m talking to you!

- Tidy your stuff up!

- Give your aunt your hand.

- Children do not interrupt when adults are talking!

Children’s opinions and feelings are not taken seriously by adults:

- Don’t talk nonsense!

- Don’t be so silly.

- Don’t be such a baby!

- It’s all kid’s talk.

Adults threaten or shame children:

- If you don’t eat up, you don’t get dessert!

- Aren’t you ashamed?

- Do I have to scold you first?

- You’re in for a real treat!

And adults show that they don’t think children are very smart:

- This is not for children!

- You’re too small for that.

- You can’t judge that at all.

- What do you know? You haven’t experienced anything yet!

Adults often talk badly about children when they are not there. Or they give answers when children are asked something and could answer themselves. Or they put children under pressure. And sometimes, children are simply ignored by adults. In Germany, children usually have to talk formally to adults, but they are usually addressed casually. In order to take children less seriously, adults say that children are “cute” or “sweet”. Or they call them belittling nicknames. If someone does something silly or stupid, they are called “childish”. Children are often touched by adults without being asked if they want to. Or they are even beaten.

Explanation: In German, the diminutive form has a discriminatory effect. It is mainly used against children. Here the girl defends herself by making her grandmother small as well.

© Natascha Welz

The “Anti-Adultist Manifesto” of a 17-year-old boy from Spain also contains the following examples:

- To deny you your own choices if you want to wear earrings, for example, or to forbid you to go to certain places or to wear certain clothes, that is adultism.

- Telling you that you are moody because you refuse to do, eat or think certain things that you would never accuse an adult of, that is adultism.

- Denying you answers to basic questions about sexuality, politics or religion, or lying to you because you are supposedly not mature enough, that is adultism.

- Exploiting you through junk contracts as a trainee or “to gain experience” because of your young age, that is adultism.

- To label young people as hooligans, drug addicts, alcoholics or good-for-nothings and to spread this in a multitude of films and series, that is adultism.

- Punishing young people for actions that would never be held against an adult, that is adultism.

- Forcing you to behave in a certain way without giving you the reasons, that is adultism.

- Denying you rights by not recognising you as a human being with a human mind, a human body and the ability to think, decide and feel…, all this is adultism.

You can find the manifesto in Spanish here: https://distripolaris.noblogs.org/files/2015/04/El-Manifiesto-Antiadultista-con-e.pdf

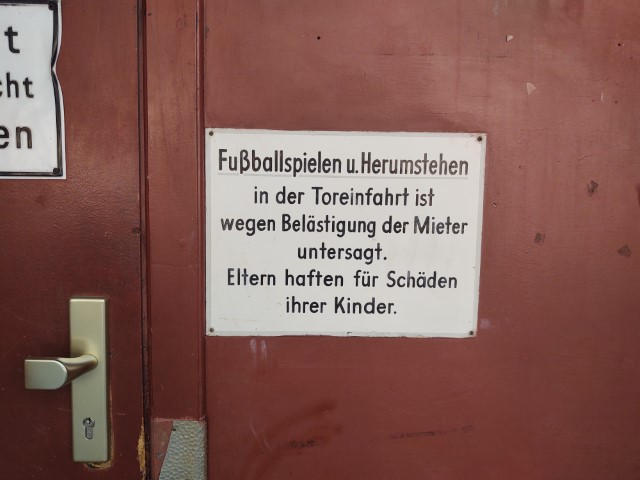

Examples of adultism can be found in the family, at school, in youth welfare, in the doctor’s office, in laws or on the street. For example, only some children have a say in where they go on holiday. Pupils very rarely have a say in what they want to learn. During the Corona years, children were hardly ever asked for their opinion. They always got the short end of the stick. Teachers control children because they want to protect them. Doctors say that children have to be able to do certain things with a certain age. Children up to the age of 13 are not allowed to earn money in Germany, even if they want to. Children are not asked when something new is to be built in their neighbourhood. Everywhere there are roads for adults’ cars. At the same time, in many places there are signs forbidding children to play ball.

Maybe you know such signs, too? We find them quite adultistic. Since 2011, by the way, “children’s noise” can no longer be punished in Germany.

Philip Meade (CC BY 2.0 Licence)

There are many more examples where children are disadvantaged or disregarded. Which ones do you know from your own life?

We think that these examples are “adultist”. Our society has been adultist for a very long time. Our parents and our ancestors also experienced adultism when they were young. But not only adults can be adultist towards children. Children and youths can also be adultist towards younger people. For example, when they tease or pick on younger people because of their age.

Many people don’t even realise that adultism exists or don’t see it as a problem. This is because adultism is so common: almost all people have been used to it since childhood. For all of us, adultism is quite normal, so to speak. That is why adultism is not talked about or researched much in schools and universities. However, some adults have made adultism an issue in recent years. And young people have been upset about adultism for a long time, even if they don’t use the word.

© Natascha Welz

Adultism can have many different effects on children. For example, they may become insecure, feel helpless or doubt themselves. Other children are frustrated or become angry. Some children resist adultism. Others withdraw and become quiet or sad. Some are mean to weaker children. Nevertheless, most children try to get along with adults in everyday life somehow.

Adults are not always deliberately adultist. Sometimes they just don’t think. Sometimes they want to feel comfortable. Sometimes they think they have to worry less by controlling children. Sometimes they have no choice themselves because they have no idea how they could do things differently. Only very few really want to harm children.

The word adultism comes from “adult”. The suffix “-ism” shows that people believe that adults are better than children. Adultism is a form of ”discrimination”. The word means that some people have more power than others and therefore have advantages. Discrimination also means that the less powerful people are devalued and treated badly. Discrimination also comes in other forms. For example, women often have less power than men, Black people have less power than White people and poor people have less power than rich people. These forms of discrimination also have consequences for children. So, every child goes through their own distinct experiences. For example, girls go through different experiences than boys. And Black girls go through different experiences than White girls. Therefore, discrimination is experienced differently by everyone.

© Natascha Welz

Ideally, people are not allowed to be discriminated against. In fact, there are various laws against discrimination. For example, Germany has had the Allgemeine Glechbehandlungsgesetz (General Equal Treatment Act) since 2006. Unfortunately, this law deals with many types of discrimination, but not with adultism. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child exists specifically for children since 1989. We will write more about this later.

We think it is important to talk and write about adultism. Because we have experienced that many young people are eager to talk about it. Finally, they find a word for something they experience every day. And having this word is also useful to stand up against adultism.

What do you think is just between adults and children, and what do you think is not?

We want to change relationships between adults and children. We want adults to share their power with children. We want children to have their rights and a say. We want to end discrimination. Then young and older people would have a better life.

When did adultism start?

Adultism is nothing new. Many thousands of years ago, adults started to rule over children. This was at a time when people no longer roamed around with their families and animals. Instead, they stayed in one place (=they became “settled”). Different work tasks were divided among the family members at that time. Older children had to look after their younger siblings. They also had to do housework. Usually, it was the father who ruled over the children (and also the women).

© Natascha Welz

Since then, many ideas have developed about how children should be and what children should do. Among other things, “initiation rites” were introduced: This was a kind of test that children had to pass in order to be allowed to be “adult”. Often these tests were dangerous or painful. Adults wanted to control children by frightening them. Some initiation rites have survived until today. For example, communion or confirmation in church.

About 3000 years ago, there were large societies in countries that are now called, for example, China, India, Greece, Italy or Mexico. There, it was mainly laws and courts that contributed to adultism. Adolescents could be expelled from the family if they did not “behave”. Babies could be killed without their parents being punished. Fortunately, that is different today.

Especially in Europe, children have not been treated well over the last thousand years. In the name of religions, children were allowed to be beaten with a stick. This is because children should behave exactly as it is written in the “holy books”. One such book is the Bible, for example. Beating was called “chastisement”, although it is actually “violence”. Parents also decided who their children should marry and what profession they should learn.

Europeans began to conquer the continents of Africa, America and Asia with ships about 500 years ago. They believed they could simply rule over the people who had been living there for a long time. They made them work for them and tortured them. They brought things to Europe that did not actually belong to them. This is called “colonisation”, it lasted until after the Second World War and continues to have an effect today. The people there were treated particularly badly. Many millions of people in the colonised countries died as a result of the brutal exploitation or were murdered in wars.

The Europeans claimed that the people living there were like children. They believed that they could therefore rule over these people. They called their home countries “mother countries”. Yet many of these societies originally had a better way of dealing with children than those in Europe. For example, children were almost never punished and they were allowed to do much more. So, Europeans could have learned something from them.

© Natascha Welz

About 300 years ago, however, the nature of adultism in Europe began to change. At that time, many ways of looking at things changed. For example, that the sun does not revolve around the earth, but the other way around. This period is called the “Enlightenment”. Some adults behaved less harshly towards children. Children occasionally had more room to play. Adults invented “education” at that time. They wanted children to learn more and develop healthier. Nevertheless, education always went according to the adults’ ideas. It was a bit like trying to tame a wild animal. Children were still not free and were not allowed to have a say. Their wishes were not taken seriously. So they had no choice but to conform. Customised institutions were even created for “education”, with specially trained adults. Namely kindergartens and schools. But also homes and prisons.

Adultism today

Adultism today manifests itself in many different situations. We have already described some of them at the beginning.

© Natascha Welz

In the family, children are completely dependent on their parents. Parents usually dictate when and where children have to do something. For example: get up, go to sleep, eat, play, learn or have free time. Some parents are mean or even violent to children without anyone outside the family noticing. This can also happen to children living in a home or with foster parents. It happens especially often to children from poor families or to “disabled” children. In most countries there are laws to prevent this. One example from Germany is the right to non-violent upbringing. However, most children are not very familiar with laws, nor are the laws explained to them. They usually do not know that they have rights or who to turn to. It is very difficult for them to redeem their rights.

Have you ever turned to an adult you trust in an emergency situation? This could also be someone at the youth welfare office or a counselling centre? Do you know how to reach them in an emergency? In Germany, on the family portal you can find some emergency numbers and contact points: https://familienportal.de/familienportal/lebenslagen/krise-und-konflikt/krisetelefone-anlaufstellen. In the US, UK, Australia or other countries where English is spoken, there are other independent child and youth emergency services!

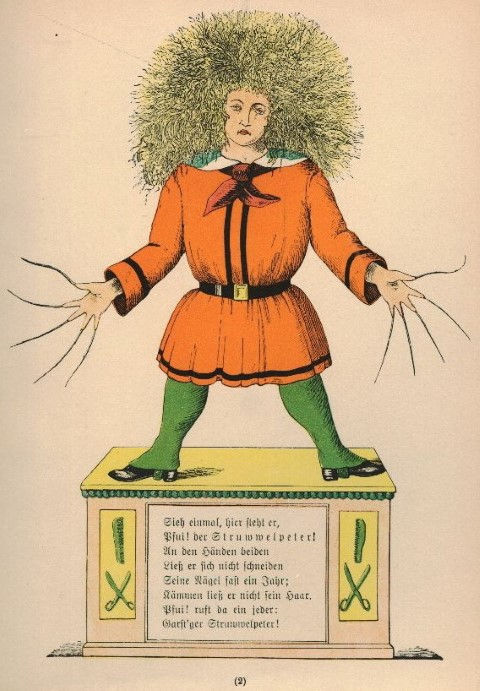

public domain

Family education uses narratives that grandparents pass on to parents and they pass on to children. These include, for example, fairy tales in which children are beaten, burned or killed for not behaving properly. This is meant to scare the children. Some children’s books and songs are also meant to intimidate children. A children’s rights activist named Ellen Key therefore demanded a special right more than 100 years ago: children should be allowed to choose their parents themselves.

How would you like it if you could choose your parents yourself?

Adultism also plays a big role at school. Teachers have a lot of power. They can decide about almost everything that happens in the classroom. They decide what, where and when students learn. They judge students and give them grades. Therefore, pupils often do not work well together, but against each other. What children are supposed to learn at school is often not interesting for them. They often ask themselves completely different questions. Besides, who says that teachers can’t learn something from pupils? Until about 50 years ago, teachers in Germany were even allowed to beat pupils.

Teachers themselves are probably afraid that everything will go haywire in class. Then they can no longer control the pupils. In schools, children are supposed to be educated to become good citizens and hard workers. When teachers fail to do this, other adults say that they are not doing their job well. Many children do not want to go to school. In Germany and many other countries, however, children have to go to school (= compulsory education). Yet schools could be quite different. They could respect more the feelings, interests and wishes of the pupils. We will come back to this later.

© Natascha Welz

Adultism is also often present in laws, in court and in politics. Many laws discriminate against children and young adults. For example, many laws say that young people can be paid less than elder people for the same work. Children are also not allowed to participate in drafting laws.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child promises many good things to children. For example, children’s opinions are to be heard when adults make decisions about things. In addition, children are to be heard and supported in court. However, the Convention on the Rights of the Child also states that adults may continue to decide whether, when and on what children are heard. And when children are heard, their opinion often counts less than that of adults. This can have particularly blatant consequences. For example, when children, parents and doctors argue about whether a child should have an operation. The child’s opinion is sometimes listened to, but usually not taken very seriously.

© Natascha Welz

Only when people are no longer “minors”, i.e. turn 18, do they have full rights. Some people therefore want to rewrite the Convention on the Rights of the Child. It would be best if children also participated in rewriting it. Politicians in Germany are currently arguing about whether children’s rights should be included in the Basic Law.

Children are not allowed to vote or to be elected. This means that they have no influence on political decisions. But there are other reasons why young people have little to say in politics. One reason is that most children find the nature of politics boring. Politicians use difficult language and talk for a long time. And the issues often do not interest young people. Another reason is that people in society are getting older. This means that more older people vote than younger people and therefore have more power.

Would you like to be able to vote? What would change if all children were allowed to vote?

There are other places where adultism happens. For example, sometimes children are not allowed in shops, cafés or hotels. Or there are the places where children are not allowed to play ball or young people are not allowed to meet. Most of the time adults say it is because children or young people might be noisy or dangerous. Or they might steal or break something.

Adultism also affects the way things are built. Door handles, light switches, steps, counters, tables, chairs, toilets, sinks and signs are at adult height. Most cities are built for adults who can drive. Children cannot play there, only in fenced playgrounds. They always have to be taken from one place to another by adults.

Sometimes adults want to do something good for children that is nevertheless adultist. For example, when adults want to protect children from danger. We think it is important to protect children from dangers that they themselves do not see. For example, when a child runs onto a busy street with cars. But in Europe, children are protected more than necessary. For example, they are not allowed to do many things until they reach a certain age. They are only allowed to work properly from the age of 15. They are not allowed to sign a contract without the consent of their parents until they are 18.

© Natascha Welz

Adults are afraid that something could happen to children. That is why they do not allow children to do many things and control them. But this can sometimes be discriminatory. For example, when children want to work and earn money. Sometimes adults forbid children to think about anything that has to do with sex. Or they don’t talk about the subject. That is a problem. Instead, we think it is important to be able to talk openly about sex with children if it interests them. They should be supported in setting boundaries themselves. And to respect the feelings of others. Of course, adults should protect children from people who are mean to children.

Many adults think they are more valuable and better than children. They don’t take children seriously and exclude them from decisions. But children are also kept away from things that could be important. For example, they are not allowed to open a bank account themselves or buy certain things. If they call an ambulance, in some countries they don’t get help. We think it’s unjust if these things are only made dependent on age. Because younger people can also be smart enough to do these things. Age doesn’t say much about what someone knows or can do.

Sometimes adults want to “exploit” children. This means that children are supposed to do something for them and get nothing in return. For example, children are asked to pose for a photo. The photo is printed in a book. The photographer gets money for the photo, but the children get nothing.

When adults destroy the earth, that is also adultism. In the future, the children of today will probably have big problems because of this. Because adults don’t take good care of the earth. Climate change in particular is a huge problem, first and foremost in poor countries. But children need nature and the environment to grow up healthy. For example, they need clean water, fresh air, plants and animals to live. In some countries, children already grow up unhealthy or have to die early.

Do you know Fridays for Future, the Last Generation or any other group of young people who are committed to the earth, nature or the environment?

Marco Verch, Flickr (CC BY 2.0 licence)

Why is there adultism?

So, let’s move on to the question of why adults are adultist. Why do they think that children always know and can do less than they do? Why do they not listen to children or take them seriously? Why do they want to use or exploit children just because they are younger or smaller? Why do they think that children are less important than adults? Many things have contributed to this.

Over the past centuries, a certain image of children has spread:

- Children only think about themselves.

- Children cannot understand anything difficult.

- Children do not pay attention.

- Children don’t do things “right”.

- Children are wild and unjust.

All this may be true sometimes. But it applies just as much to adults. And as you surely know: children can also be completely different!

But why do adults have such ideas? There are many reasons for this. One reason is that psychologists did research on some children in the last century. They thought they knew something about children. They transferred this knowledge to all children. The researchers did not take into account that children can be different in other places and at other times. From them, other adults have learned that children should be like this and like that. So, they also think that all children of a certain age know and can do the same. The older the more. They then no longer ask the children they actually deal with. They are no longer interested in what the children can already do and how they see the world.

Adults also often want their children to be like them. They want their children to have the same experiences. Or learn the same profession. But each person has to make their own experiences. And go their own way.

Some adults are in a difficult situation themselves. Maybe they don’t have enough money. Maybe they are stressed. But maybe they simply haven’t learned any better. Most adults were treated adultistically in their childhood, too.

© Natascha Welz

But adults are sometimes lazy and don’t want to think. They like being “grown up”. In society, it is normal to be an adult. Nobody gets upset about it. So they can easily rule over children. They think that children must always be led by them. Adults therefore don’t have to explain why they demand this and that from children. One consequence is that children want to become adults themselves as soon as possible. Because then they are allowed to do the same.

Which adults do you know who do not behave in an adultist way? What do they do differently?

It is unclear when adultism started. We have already written about why people divided themselves into groups of children and adults. And that these were treated differently. Adults then gradually acquired power over children. This power was always passed on. We have seen what has contributed to this: language, fairy tales, school, rules, laws and politics, for example. Today, adultism is almost everywhere in the everyday lives of children and adults.

Explanation: In day-care centres and kindergartens there is often a morning circle. Children come together there to get in the mood for the day.

© Natascha Welz

Adultism is bad for children. But it is not necessarily good for adults either. For example, it makes their relationship with children worse. Living together is then more stressful.

Some adults wonder if society needs to be adultist. Many children and young people also want to end adultism. That makes sense. Because that could help children trust themselves more. It could also give them a better feeling about life. They could feel for themselves what is good for them. And they could then protect themselves better.

Explanation: When casting for a film or series, actors have to prove that they are suitable for a certain role.

© Natascha Welz

Of course, there would still be differences between children and adults. But adults would no longer rule over children. Children would be taken seriously in everything they think and do. Children would no longer be treated as inferior, but as equals. Children would have a say in everything. Children and adults would then be partners. There would no longer be upbringing, but a relationship!

How do you imagine a society without adultism? What would the relationships between adults and children look like?

What can be done against adultism?

There have been children, young people and adults who have been resisting adultism for a long time. Some do it consciously. Some do it more casually. Some do it alone, some in a group. But they rarely use the word “adultism”. They don’t necessarily need to, either.

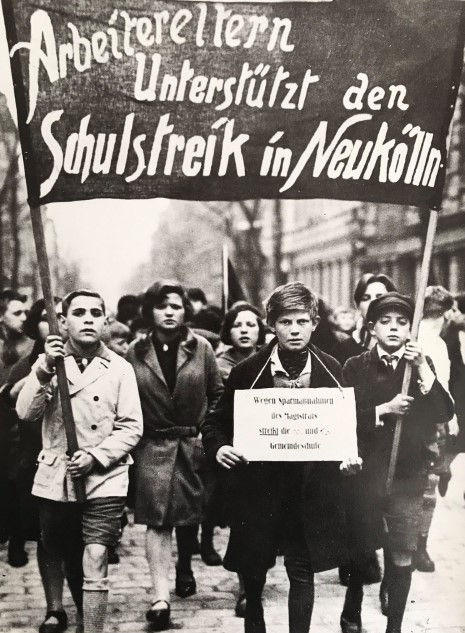

public domain

For example, students got together during the Corona period. They fought back against their bad treatment. They complained that they were not listened to. Some wrote a petition and also asked adults to support them. Among other things, they wanted more masks and rapid tests for schools. They wanted to be consulted on the protective measures in their schools. 150,000 people signed the petition. Afterwards, politicians listened to them. We still have to see if anything changes.

Have you ever campaigned for something similar? How did you do it?

Many children and adults have already been annoyed by school. More than 100 years ago, adults developed new types of schools. There, pupils were more free. They could decide what they wanted to learn and when they wanted to learn it. Pupils not only learned from teachers, but also from other pupils. Or from other people in the city. Some of these schools still exist today or are being newly founded. They are called “free democratic schools” or “free alternative schools”. Now and then, there were even attempts to abolish compulsory education. Children could then also learn at home. However, one has to be careful. Because one’s own parents are not always the better teachers. Maybe in future there will be a self-determined “right to education” instead of compulsory schooling?

© Summerhill School, Leiston, Suffolk, GB

Normal schools have also learned. Children’s rights are becoming more important there. In some schools there are class councils or student parliaments. This means that pupils should actually be able to make a lot of decisions in their school. Unfortunately, some teachers do not allow this or use the class council for other purposes. For example, to have silence in the classroom again. Or to catch up on lessons.

What would your ideal school or form of learning look like? What distinguishes it from “normal” schools and forms of learning?

In homes and foster families in Germany, children have a “right to complain”. Children are allowed to complain to adults if they find something unjust. Or if they are treated badly. There can be a confidant in the facility for this purpose. Or outside the facility, for example in an ombudsman’s office. However, the right to complain is quite new and has not yet been implemented in some places. But that has to happen quickly now.

Child protection is also often adultist. But that doesn’t always have to be the case. For that, it is important that children are strengthened. They should not be confined, controlled and punished. Instead, adults must support children in recognising dangers. Children should be able to criticise. Adults must give children responsibility. They must trust children to set their own limits and support them in doing so. And they must inform children about their rights. In addition, the circumstances in which children grow up must be improved. For example, there must be an end to child poverty or violence. And children must receive help quickly if something happens to them. Nowadays, all this must also be taken into account on the internet and in computer games.

It is important that children and adults know about children’s rights. This is the only way children know what they are entitled to. In other words, what they are allowed or should get. Surveys in Germany show that this is unfortunately not often the case. Only every seventh child knows several children’s rights. Among adults, the figure is even lower. Almost all countries in the world have signed the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. In doing so, the countries have promised to implement children’s rights. The 41 children’s rights are sometimes summarised. Every child has a right to:

- Non-discrimination

- Health

- Education

- Play and leisure

- Freedom of expression, information and hearing

- Non-violent education

- Protection in war and on the run

- Protection from economic and sexual exploitation

- Parental care

- Disability care

Which children’s rights do you already know? What other children’s rights would you like to see?

© Natascha Welz

We mentioned before that the United Nations children’s rights are not perfect. They should be developed further by children. Nevertheless, it is good that they exist. As you surely realize yourself, children’s rights are not always implemented. In order for them to be better implemented, many more adults and children need to stand up for them.

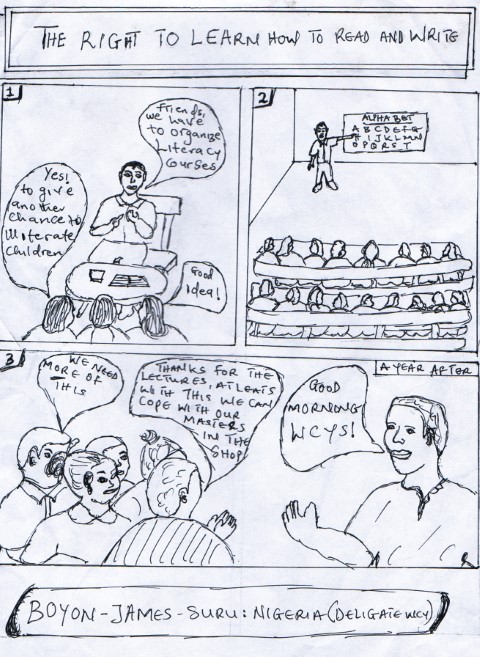

In Africa, Asia and South America, working children have come together in groups. Often several hundred young people have assembled. And these groups are in contact with other groups. They talk about what is good and bad about their work. They think together about how they can do their work better. They want to work and earn money. But they want to be treated well, not have to put themselves at risk and be paid properly. They fight together against adults who treat them badly. These “children’s movements” are also supported by adults. But still, the children have the say. The adults help them to do what they cannot or are not allowed to do themselves. For example, signing a contract. Sometimes the children’s movements are even listened to by politicians. These young people almost never use the word adultism. Nevertheless, they contribute to fighting adultism.

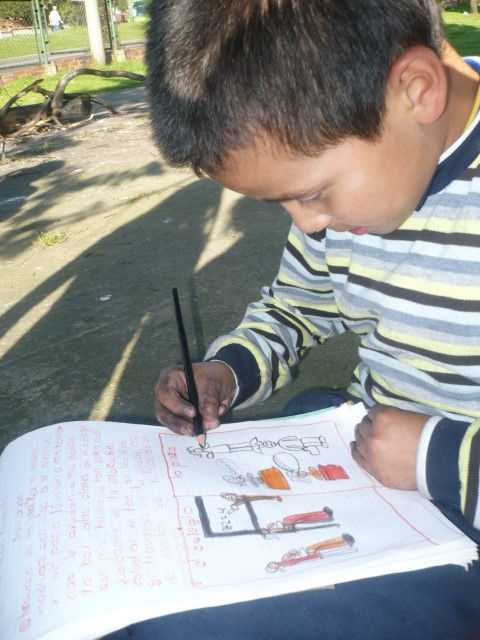

© Callescuela

Other examples of children and young people working alone or with others for a better life and a better future are:

- Greta Thunberg and Fridays for Future

- The Last Generation

- Jugendliche ohne Grenzen (Youth without borders)

- Never Again MSD

- Felix Finkbeiner

- Malala Yousafzai

- Emil Rustige

- Ahed Tamimi

- Makkala Panchayats

- Children’s movements, such as UNATSBO, MAEJT or MOLACNATS

How and what did these children and young people do? Search for their names or groups on the internet!

Stefan Müller, Wikipedia (CC BY 2.0 licence)

In Germany there was also the Naiv Kollektiv. Younger and older people give joint lectures and workshops against adultism. They interview people and write texts. They use the word “adultism” with full intention. Here you can watch their explanatory video on YouTube: https://youtu.be/iITfj-kpnOQ.

Sometimes children and youth also spontaneously stand up for something because something bad has happened. They are allowed to do that. Because children have the right to demonstrate. This was the case in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, in 2018: Reckless drivers had already hit several children. Some of them died. Then thousands of young people demonstrated and controlled the drivers. The government didn’t like this very much.

© Natascha Welz

Another example is children who have little money and no home or family. They often band together to survive better. They show each other how to get food or medicine. They protect each other at their sleeping places. Some even grow vegetables together to have more and better food. They share the work and also share their things. For example, in Peru or in Senegal.

You see: children can join forces with others. Together they are stronger. If you want to watch a documentary about children and young people who stand up for something: Look for the film Demain est à nous (“Tomorrow belongs to us”) by filmmaker Gilles de Maistre. Or the film Power to the Children by filmmaker Anna Kersting.

© Gilles de Maistre

© Anne Kersting

It is just as important for adults to think about their power. Without children having to be there. Adults need to think:

- How much power do I have as an adult?

- Where do I exercise power?

- How can I renounce power over children?

- How can I share power with children?

Adults should also ask themselves what their environment and everyday life are like:

- How much space do children have to move around independently and carefree?

- How much free time do children have?

- Which things can children use freely?

- Where can children influence decisions?

And they have to think about how their lifestyle will affect children or in the future:

- Do they have a healthy environment, plants and animals?

- Can they live well?

- Will children in the future have the same conditions as today?

- Who speaks for the children who are not yet born?

Manfred Liebel (CC BY 2.0 licence)

© AMWCY & enda tm jeunesse action

As part of the KinderTheaterGesellschaft project of GRIPS Werke e.V., young people aged 9 to 12 have made demands:

How adults should deal with us!

- If we have problems, first ask what’s wrong with us instead of helping straight away. If we don’t have any ideas, suggest some.

- Think before you shout.

- You can just ask us nicely to listen instead of freaking out right away.

- You say something loudly so that we understand it better. But we don’t understand it better when you are loud.

- Adults should want to understand what exactly we want and say what they don’t want and then find a solution that both find okay.

- Comparisons with elders or your own childhood are useless. That was a different age. The world is spinning mega fast.

- Say what we are still allowed to do, rather than what we have to leave out now.

- Even if you are busy, listen properly for a moment.

- Why don’t you try out the tips you give us yourself (e.g. a day without a mobile phone)?

- Don’t say stupid or private things in front of the whole group. Rather say them alone at the end. Some children get really sad and angry.

- When we have a laughing fit, don’t ask in front of everyone what was so funny and want to laugh along, maybe it was something private.

- Adults should ask if they can say things about us.

- In conversations, when an adult leans over because the child is smaller, this feels uncomfortable.

- Adults should not pretend to know everything.

- Adults should explain things to children, look carefully and be just.

Excerpt from: How to deal with us! Wie Erwachsene mit uns umgehen sollen! (free download at www.gripswerke.de/veroeffentlichungen). Authors: Alice, Amnon, An-Nhien, Anna, Atay, Carlotta, Cassandra, Cosima, Deniz, Ella, Emily, Felia, Hana, Helene, Igballe, Jette, Jolanda, Julia, Julie, Justin, Kaan, Kiara, Lea, Leah, Lena, Lennox, Levy, Linda, Lotti, Luis, Luka, Madita, Mai, Marie, Mateo, Mia, Mila, Milan, Mine, Mir, Mona, Nike, Pauliana, Rayan, Razen, Sara, Shira, Shirali, Sophie, Tom, Vinzenz, Yelena & Yuri. Edited by Wiebke Hagemeier.

In the federal elections, people in Germany are only allowed to vote from the age of 18. There have been adults and children who want children to be able to vote for years. They have made different proposals. Some want children to be allowed to vote from the age of 16. Others want children to be allowed to vote from the age of 12 or 14. Some even want children to be able to vote after birth: that is, of course, only when the child decides to do so itself. Some want parents to be able to vote for their child in the meantime.

Many adults say that children should not vote. They say that children don’t understand anything about politics. Yet there are many adults who don’t understand politics themselves. And they can still vote. We think that there are no good arguments to stop children from voting. After all, they are also affected by political decisions.

© Natascha Welz

An important question is whether adults should speak for children. Or whether children should always speak only for themselves. We believe that adults sometimes have to do that. But they should always talk to the children before and after. And they must give the children the opportunity to speak their minds everywhere if they want to. This can also be at an adult meeting, for example.

In which cases should adults be allowed to speak on your behalf, and in which cases should they rather not?

Being against adultism does not mean that children now rule over adults. Or that it doesn’t matter what children do. Adults have rights too. After all, we all have to get along together if we want to have a really good life.

It is about people being just to each other. It is about adults and children talking and listening to each other. That they make decisions together and share power. Children should be taken seriously. Their opinion should be at the forefront when it comes to important decisions that affect them. This is also stated in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Article 3 deals with the primacy of the “best interests of the child”.

We hope you got along with the summary of our thick book. Maybe you can talk about it with friends? And we hope that you have trustworthy adults around you with whom you can discuss adultism if you want to. Maybe this will already change something small. And after all, adults can continue to grow – sometimes beyond themselves!

Glossary

- A society is a whole lot of people living together. For example, in a country, a place or a region.

- The United Nations is an association of almost all the states in the world. They have declared that they want to work together here to make the world a better place.

- Pedagogues are people who work with children and young people and want to educate them.

- A person has power when he or she can control other people, animals or things. But power can also be used to defend oneself.

- The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child contains 41 articles that promise children rights to protection, provision and participation.

- A religion is a body of thought that a group of people believe in together. It contains many rules and commandments. In a religion there is a god, a goddess or several gods.

- Citizens are the people who belong to a state. How much they can have a say and participate in decision-making varies.

- Important decisions are made in politics. For example, who gets how much of what. Or whether a new road or a playground is to be built.

- A person is called a “minor” if he or she is under 18 years old. The word “minor” is rather insulting.

- Almost all countries have a Basic Law (often called a “constitution”), which contains the most important rules for living together.

- In many countries, people go to vote every few years to determine who gets to govern.

- Sex has several meanings. Here we mean showing genitals, playing with them, also touching each other, giving each other pleasure or “sleeping” together.

- In climate change, the earth continues to warm over a long period of time. This is dangerous for all humans and wildlife. For example, coal-fired power plants and fat cars contribute to climate change.

- Psychologists are people who deal with the feelings, thoughts and behaviour of other people and sometimes help them with problems.

- People rule over other people when they exercise a lot of power over them over a long period of time.

- In a petition, people get involved in a cause and ask others to support it. They then hand the petition to politicians and hope (sometimes in vain) for change.

- An ombudsman’s office helps you (and other people) to realise your rights. The staff will advise you and sometimes accompany you to a court hearing.

- When people disagree with something and express this in some way, they criticise.

- People demonstrate when they take to the streets together and stand up loudly or with signs for or against something.

- Sometimes people can be convinced with good arguments (=reasons for or against something).

About the authors and the illustrator

Manfred Liebel was Professor of Sociology at the TU Berlin until 2005 and has led the Master’s programme “Childhood Studies and Children’s Rights” at the FU Berlin and the FH Potsdam from 2007 to 2021. He is the father of two children, who are now 25 and 31 years old, and lives in Berlin.

Philip Meade is a lecturer in the Master’s programme mentioned above. He was a children’s rights representative in Berlin youth welfare until 2020, and now works freelance on children’s rights and adultism. He lives with 35 people between the ages of 1 and 66 in a Berlin house project.

Natascha Welz aka “Tasche” is an art educator and cartoonist. She draws with a sharp pen for educational media, illustrates school books or organises seminars for professionals in early childhood education on art and STEM topics. She lives in Berlin with her four children.

Cover text

In our society, children are often disregarded, regulated and disadvantaged. We call this adultism. This book explains the topic in simple language and with drawings and photos. We show how young people are affected by adultism. In the family, at school, in traffic, in politics. Through rules and prohibitions in everyday life.

But we also give examples of what young people can do against adultism. And how adults could share their power with children. We think: Children should already be allowed to vote. Children’s rights must be made known and implemented. And politics must change so that children find it interesting.

This would contribute to a world in which everyone is taken seriously and is involved in shaping life together. No matter how old they are.

Imprint

Online version 2023 under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

Print version © 2023 by Bertz + Fischer GbR, Franz-Mehring-Platz 1, 10243 Berlin.

https://bertz-fischer.de

ISBN 978-3-86505-775-4

The drawings for this publication were produced with the kind support of Deutsches Kinderhilfswerk e.V..